Many-worlds interpretation

Many-worlds is an interpretation of quantum mechanics that asserts the objective reality of the universal wavefunction, but denies the reality of wavefunction collapse, which implies that all possible alternative histories and futures are real —each representing an actual "world" (or "universe"). It is also referred to as MWI, the relative state formulation, the Everett interpretation, the theory of the universal wavefunction, many-universes interpretation, or just many worlds.

The original relative state formulation is due to Hugh Everett in 1957.[2][3] Later, this formulation was popularized and renamed many-worlds by Bryce Seligman DeWitt in the 1960s and '70s.[1][4][5][6]

Many-worlds claims to reconcile how we can perceive non-deterministic events, such as the random decay of a radioactive atom, with the deterministic equations of quantum physics. Prior to many-worlds, reality had been viewed as a single unfolding history. Many-worlds, rather, views reality as a many-branched tree, wherein every possible quantum outcome is realised.

In many-worlds, the subjective appearance of wavefunction collapse is explained by the mechanism of quantum decoherence. By decoherence, many-worlds claims to resolve all of the correlation paradoxes of quantum theory, such as the EPR paradox[7][8] and Schrödinger's cat,[1] since every possible outcome of every event defines or exists in its own "history" or "world". In layman's terms, there is a very large—perhaps infinite[9]—number of universes, and everything that could possibly have happened in our past, but didn't, has occurred in the past of some other universe or universes.

The decoherence approach to interpreting quantum theory has been further explored and developed[10][11][12] becoming quite popular, taken as a class overall. MWI is one of many Multiverse hypotheses in physics and philosophy. It is currently considered a mainstream interpretation along with the other decoherence interpretations and the Copenhagen interpretation.

| Quantum mechanics | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Uncertainty principle |

||||||||||||||||

Introduction · Mathematical formulations

|

||||||||||||||||

Outline

Although several versions of many-worlds have been proposed since Hugh Everett's original work,[3] they all contain one key idea: the equations of physics that model the time evolution of systems without embedded observers are sufficient for modelling systems which do contain observers; in particular there is no observation-triggered wavefunction collapse which the Copenhagen interpretation proposes. Provided the theory is linear with respect to the wavefunction, the exact form of the quantum dynamics modelled, be it the non-relativistic Schrödinger equation, relativistic quantum field theory or some form of quantum gravity or string theory, does not alter the validity of MWI since MWI is a metatheory applicable to all linear quantum theories, and there is no experimental evidence for any non-linearity of the wavefunction in physics.[13][14] MWI's main conclusion is that the universe (or multiverse in this context) is composed of a quantum superposition of very many, possibly even non-denumerably infinitely[9] many, increasingly divergent, non-communicating parallel universes or quantum worlds.[6]

The idea of MWI originated in Everett's Princeton Ph.D. thesis "The Theory of the Universal Wavefunction",[6] developed under his thesis advisor John Archibald Wheeler, a shorter summary of which was published in 1957 entitled "Relative State Formulation of Quantum Mechanics" (Wheeler contributed the title "relative state";[15] Everett originally called his approach the "Correlation Interpretation", where "correlation" refers to quantum entanglement). The phrase "many-worlds" is due to Bryce DeWitt,[6] who was responsible for the wider popularisation of Everett's theory, which had been largely ignored for the first decade after publication. DeWitt's phrase "many-worlds" has become so much more popular than Everett's "Universal Wavefunction" or Everett-Wheeler's "Relative State Formulation" that many forget that this is only a difference of terminology; the content of both of Everett's papers and DeWitt's popular article is the same.

The many-worlds interpretation shares many similarities with later, other "post-Everett" interpretations of quantum mechanics which also use decoherence to explain the process of measurement or wavefunction collapse. MWI treats the other histories or worlds as real since it regards the universal wavefunction as the "basic physical entity"[16] or "the fundamental entity, obeying at all times a deterministic wave equation".[17] The other decoherent interpretations, such as consistent histories, the Existential Interpretation etc., either regard the extra quantum worlds as metaphorical in some sense, or are agnostic about their reality; it is sometimes hard to distinguish between the different varieties. MWI is distinguished by two qualities: it assumes realism,[16][17] which it assigns to the wavefunction, and it has the minimal formal structure possible, rejecting any hidden variables, quantum potential, any form of a collapse postulate (i.e. Copenhagenism) or mental postulates (such as the many-minds interpretation makes).

Decoherent interpretations of many-worlds use einselection to explain how a small number of classical pointer states can emerge from the enormous Hilbert space of superpositions have been proposed by Wojciech H. Zurek. "Under scrutiny of the environment, only pointer states remain unchanged. Other states decohere into mixtures of stable pointer states that can persist, and, in this sense, exist: They are einselected."[18] These ideas complement MWI and bring the interpretation in line with our perception of reality.

Many-worlds is often referred to as a theory, rather than just an interpretation, by those who propose that many-worlds can make testable predictions (such as David Deutsch) or is falsifiable (such as Everett) or by those who propose that all the other, non-MW interpretations, are inconsistent, illogical or unscientific in their handling of measurements; Hugh Everett argued that his formulation was a metatheory, since it made statements about other interpretations of quantum theory; that it was the "only completely coherent approach to explaining both the contents of quantum mechanics and the appearance of the world."[19]

Interpreting wavefunction collapse

As with the other interpretations of quantum mechanics, the many-worlds interpretation is motivated by behavior that can be illustrated by the double-slit experiment. When particles of light (or anything else) are passed through the double slit, a calculation assuming wave-like behavior of light can be used to identify where the particles are likely to be observed. Yet when the particles are observed in this experiment, they appear as particles (i.e. at definite places) and not as non-localized waves.

Some versions of the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics proposed a process of "collapse" in which an indeterminate quantum system would probabilistically collapse down onto, or select, just one determinate outcome to "explain" this phenomenon of observation. Wavefunction collapse was widely regarded as artificial and ad-hoc, so an alternative interpretation in which the behavior of measurement could be understood from more fundamental physical principles was considered desirable.

Everett's Ph.D. work provided such an alternative interpretation. Everett noted that for a composite system – for example a subject (the "observer" or measuring apparatus) observing an object (the "observed" system, such as a particle) – the statement that either the observer or the observed has a well-defined state is meaningless; in modern parlance the observer and the observed have become entangled; we can only specify the state of one relative to the other, i.e. the state of the observer and the observed are correlated after the observation is made. This led Everett to derive from the unitary, deterministic dynamics alone (i.e. without assuming wavefunction collapse) the notion of a relativity of states.

Everett noticed that the unitary, deterministic dynamics alone decreed that after an observation is made each element of the quantum superposition of the combined subject-object wavefunction contains two "relative states": a "collapsed" object state and an associated observer who has observed the same collapsed outcome; what the observer sees and the state of the object have become correlated by the act of measurement or observation. The subsequent evolution of each pair of relative subject-object states proceeds with complete indifference as to the presence or absence of the other elements, as if wavefunction collapse has occurred, which has the consequence that later observations are always consistent with the earlier observations. Thus the appearance of the object's wavefunction's collapse has emerged from the unitary, deterministic theory itself. (This answered Einstein's early criticism of quantum theory, that the theory should define what is observed, not for the observables to define the theory).[20] Since the wavefunction appears to have collapsed then, Everett reasoned, there was no need to actually assume that it had collapsed. And so, invoking Occam's razor, he removed the postulate of wavefunction collapse from the theory.

Probability

A consequence of removing wavefunction collapse from the quantum formalism is that the Born rule requires derivation, since many-worlds claims to derive its interpretation from the formalism. Attempts have been made, by many-world advocates and others, over the years to derive the Born rule, rather than just conventionally assume it, so as to reproduce all the required statistical behaviour associated with quantum mechanics. There is no consensus on whether this has been successful.[21][22][23]

Everett, Gleason and Hartle

Everett (1957) briefly derived the Born rule by showing that the Born rule was the only possible rule, and that its derivation was as justified as the procedure for defining probability in classical mechanics. Everett stopped doing research in theoretical physics shortly after obtaining his Ph.D., but his work on probability has been extended by a number of people. Andrew Gleason (1957) and James Hartle (1965) independently reproduced Everett's work, known as Gleason's theorem[24][25] which was later extended.[26][27]

De Witt and Graham

Bryce De Witt and his doctoral student R. Neill Graham later provided alternative (and longer) derivations to Everett's derivation of the Born rule. They demonstrated that the norm of the worlds where the usual statistical rules of quantum theory broke down vanished, in the limit where the number of measurements went to infinity.

Deutsch et al.

An information-theoretic derivation of the Born rule from Everettarian assumptions, was produced by David Deutsch (1999)[28] and refined by Wallace (2002–2009)[29][30][31][32] and Saunders (2004).[33][34] Deutsch's derivation is a two-stage proof: first he shows that the number of orthonormal Everett-worlds after a branching is proportional to the conventional probability density. Then he uses game theory to show that these are all equally likely to be observed. The last step in particular has been criticised for circularity.[35][36] Other reviews have been positive, although the status of these arguments remains highly controversial. It is fair to say that some theoretical physicists have taken them as supporting the case for parallel universes.[37][38] In the New Scientist article, reviewing their presentation at a September 2007 conference[39][40], Andy Albrecht, a physicist at the University of California at Davis, is quoted as saying "This work will go down as one of the most important developments in the history of science."[37]

Wojciech H. Zurek (2005)[41] has produced a derivation of the Born rule, where decoherence has replaced Deutsch's informatic assumptions.[42] Lutz Polley (2000) has produced Born rule derivations where the informatic assumptions are replaced by symmetry arguments.[43][44]

Advantages

- MWI removes the observer-dependent role in the quantum measurement process by replacing wavefunction collapse with quantum decoherence. Since the role of the observer lies at the heart of most if not all "quantum paradoxes," this automatically resolves a number of problems; see for example Schrödinger's cat thought-experiment, the EPR paradox, von Neumann's "boundary problem" and even wave-particle duality. Quantum cosmology also becomes intelligible, since there is no need anymore for an observer outside of the universe.

- MWI is realist, deterministic, local theory, akin to classical physics (including the theory of relativity), at the expense of losing counterfactual definiteness. MWI achieves this by removing wavefunction collapse, which is indeterministic and non-local, from the deterministic and local equations of quantum theory.[45][46]

- MWI (or other, broader multiverse considerations) provides a context for the anthropic principle which may provide an explanation for the fine-tuned universe.[47][48]

- MWI, being a decoherent formulation, is axiomatically more streamlined than the Copenhagen and other collapse interpretations; and thus favoured under certain interpretations of Occam's razor.[49] Of course there are other decoherent interpretations that also possess this advantage with respect to the collapse interpretations.

Common objections and misconceptions

- MWI states that there is no special role nor need for precise definition of measurement in MWI, yet uses the word "measurement" repeatedly through out its exposition.

-

- MWI response: "measurements" are treated a subclass of interactions, which induce subject-object correlations in the combined wavefunction. There is nothing special about measurements (they don't trigger any wave function collapse, for example); they are just another unitary time development process.[2] This is why no precise definition of measurement is required in Everett's formulation.

- The many-worlds interpretation is very vague about the ways to determine when splitting happens, and nowadays usually the criterion is that the two branches have decohered. However, present day understanding of decoherence does not allow a completely precise, self contained way to say when the two branches have decohered/"do not interact", and hence many-worlds interpretation remains arbitrary. This is the main objection opponents of this interpretation raise, saying that it is not clear what is precisely meant by branching, and point to the lack of self contained criteria specifying branching.

-

- MWI response: the decoherence or "splitting" or "branching" is complete when the measurement is complete. In Dirac notation a measurement is complete when:

- where

![O[i]](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/0601b45d3c7df03a9b0a006bf21cd80e.png) represents the observer having detected the object system in the i-th state. Before the measurement has started the observer states are identical; after the measurement is complete the observer states are orthonormal.[3][6] Thus a measurement defines the branching process: the branching is as well- or ill- defined as the measurement is. Thus branching is complete when the measurement is complete. Since the role of the observer and measurement per se plays no special role in MWI (measurements are handled as all other interactions are) there is no need for a precise definition of what an observer or a measurement is — just as in Newtonian physics no precise definition of either an observer or a measurement was required or expected. In all circumstances the universal wavefunction is still available to give a complete description of reality.

represents the observer having detected the object system in the i-th state. Before the measurement has started the observer states are identical; after the measurement is complete the observer states are orthonormal.[3][6] Thus a measurement defines the branching process: the branching is as well- or ill- defined as the measurement is. Thus branching is complete when the measurement is complete. Since the role of the observer and measurement per se plays no special role in MWI (measurements are handled as all other interactions are) there is no need for a precise definition of what an observer or a measurement is — just as in Newtonian physics no precise definition of either an observer or a measurement was required or expected. In all circumstances the universal wavefunction is still available to give a complete description of reality. - Also, it is a common misconception to think that branches are completely separate. In Everett's formulation, they may in principle quantum interfere (i.e. "merge" instead of "splitting") with each other in the future,[50] although this requires all "memory" of the earlier branching event to be lost, so no observer ever sees two branches of reality.[51][52]

- MWI response: the decoherence or "splitting" or "branching" is complete when the measurement is complete. In Dirac notation a measurement is complete when:

- There is circularity in Everett's measurement theory. Under the assumptions made by Everett, there are no 'good observations' as defined by him, and since his analysis of the observational process depends on the latter, it is void of any meaning. The concept of a 'good observation' is the projection postulate in disguise and Everett's analysis simply derives this postulate by having assumed it, without any discussion.[53]

-

- MWI response: Everett's treatment of observations / measurements covers both idealised good measurements and the more general bad or approximate cases.[54] Thus it is legitimate to analyse probability in terms of measurement; no circularity is present.

- Talk of probability in Everett presumes the existence of a preferred basis to identify measurement outcomes for the probabilities to range over. But the existence of a preferred basis can only be established by the process of decoherence, which is itself probabilistic[35] or arbitrary.[55]

-

- MWI response: Everett analysed branching using what we now call the "measurement basis". It is fundamental theorem of quantum theory that nothing measurable or empirical is changed by adopting a different basis. Everett was therefore free to choose whatever basis he liked. The measurement basis was simply the simplest basis in which to analyse the measurement process.[56][57]

- We cannot be sure that the universe is a quantum multiverse until we have a theory of everything and, in particular, a successful theory of quantum gravity.[58] If the final theory of everything is non-linear with respect to wavefunctions then many-worlds would be invalid.[1][3][4][5][6]

-

- MWI response: All accepted quantum theories of fundamental physics are linear with respect to the wavefunction. Whilst quantum gravity or string theory may be non-linear in this respect there is no evidence to indicate this at the moment.[13][14]

- Conservation of energy is grossly violated if at every instant near-infinite amounts of new matter are generated to create the new universes.

-

- MWI response: Conservation of energy is not violated since the energy of each branch has to be weighted by its probability, according to the standard formula for the conservation of energy in quantum theory. This results in the total energy of the multiverse being conserved.[59]

- Occam's Razor rules against a plethora of unobservable universes — Occam would prefer just one universe; i.e. any non-MWI interpretation.

-

- MWI response: Occam's razor actually is a constraint on the complexity of physical theory, not on the number of universes. MWI is a simpler theory since it has fewer postulates.[49] See the "advantages" section.

- Unphysical universes: If a state is a superposition of two states

and

and  , i.e.

, i.e.  , i.e. weighted by coefficients a and b, then if

, i.e. weighted by coefficients a and b, then if  , what principle allows a universe with vanishingly small probability b to be instantiated on an equal footing with the much more probable one with probability a? This seems to throw away the information in the probability amplitudes. Such a theory makes little sense.

, what principle allows a universe with vanishingly small probability b to be instantiated on an equal footing with the much more probable one with probability a? This seems to throw away the information in the probability amplitudes. Such a theory makes little sense.

- Violation of the principle of locality, which contradicts special relativity: MWI splitting is instant and total: this may conflict with relativity, since an alien in the Andromeda galaxy can't know I collapse an electron over here before she collapses hers there: the relativity of simultaneity says we can't say which electron collapsed first — so which one splits off another universe first? This leads to a hopeless muddle with everyone splitting differently. Note: EPR is not a get-out here, as the alien's and my electrons need never have been part of the same quantum, i.e. entangled.

-

- MWI response: the splitting can be regarded as causal, local and relativistic, spreading at, or below, the speed of light (e.g. we are not split by Schrödinger's cat until we look in the box).[61] For spacelike separated splitting you can't say which occurred first — but this is true of all spacelike separated events, simultaneity is not defined for them. Splitting is no exception; many-worlds is a local theory.[46]

Brief overview

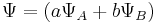

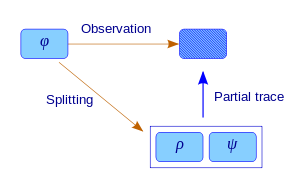

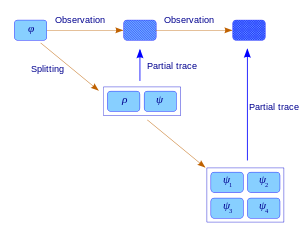

In Everett's formulation, a measuring apparatus M and an object system S form a composite system, each of which prior to measurement exists in well-defined (but time-dependent) states. Measurement is regarded as causing M and S to interact. After S interacts with M, it is no longer possible to describe either system by an independent state. According to Everett, the only meaningful descriptions of each system are relative states: for example the relative state of S given the state of M or the relative state of M given the state of S. In DeWitt's formulation, the state of S after a sequence of measurements is given by a quantum superposition of states, each one corresponding to an alternative measurement history of S.

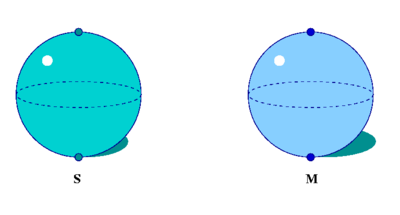

For example, consider the smallest possible truly quantum system S, as shown in the illustration. This describes for instance, the spin-state of an electron. Considering a specific axis (say the z-axis) the north pole represents spin "up" and the south pole, spin "down". The superposition states of the system are described by (the surface of) a sphere called the Bloch sphere. To perform a measurement on S, it is made to interact with another similar system M. After the interaction, the combined system is described by a state that ranges over a six-dimensional space (the reason for the number six is explained in the article on the Bloch sphere). This six-dimensional object can also be regarded as a quantum superposition of two "alternative histories" of the original system S, one in which "up" was observed and the other in which "down" was observed. Each subsequent binary measurement (that is interaction with a system M) causes a similar split in the history tree. Thus after three measurements, the system can be regarded as a quantum superposition of 8= 2 × 2 × 2 copies of the original system S.

The accepted terminology is somewhat misleading because it is incorrect to regard the universe as splitting at certain times; at any given instant there is one state in one universe.

Relative state

The goal of the relative-state formalism, as originally proposed by Everett in his 1957 doctoral dissertation, was to interpret the effect of external observation entirely within the mathematical framework developed by Paul Dirac, von Neumann and others, discarding altogether the ad-hoc mechanism of wave function collapse. Since Everett's original work, there have appeared a number of similar formalisms in the literature. One such idea is discussed in the next section.

The relative-state interpretation makes two assumptions. The first is that the wavefunction is not simply a description of the object's state, but that it actually is entirely equivalent to the object, a claim it has in common with some other interpretations. The second is that observation or measurement has no special role, unlike in the Copenhagen interpretation which considers the wavefunction collapse as a special kind of event which occurs as a result of observation.

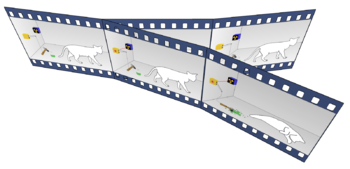

The many-worlds interpretation is DeWitt's popularisation of Everett's work, who had referred to the combined observer-object system as being split by an observation, each split corresponding to the different or multiple possible outcomes of an observation. These splits generate a possible tree as shown in the graphic below. Subsequently DeWitt introduced the term "world" to describe a complete measurement history of an observer, which corresponds roughly to a single branch of that tree. Note that "splitting" in this sense, is hardly new or even quantum mechanical. The idea of a space of complete alternative histories had already been used in the theory of probability since the mid 1930s for instance to model Brownian motion.

Under the many-worlds interpretation, the Schrödinger equation, or relativistic analog, holds all the time everywhere. An observation or measurement of an object by an observer is modeled by applying the wave equation to the entire system comprising the observer and the object. One consequence is that every observation can be thought of as causing the combined observer-object's wavefunction to change into a quantum superposition of two or more non-interacting branches, or split into many "worlds". Since many observation-like events have happened, and are constantly happening, there are an enormous and growing number of simultaneously existing states.

If a system is composed of two or more subsystems, the system's state will be a superposition of products of the subsystems' states. Once the subsystems interact, their states are no longer independent. Each product of subsystem states in the overall superposition evolves over time independently of other products. The subsystems states have become correlated or entangled and it is no longer possible to consider them independent of one another. In Everett's terminology each subsystem state was now correlated with its relative state, since each subsystem must now be considered relative to the other subsystems with which it has interacted.

Comparative properties and experimental support

One of the salient properties of the many-worlds interpretation is that observation does not require an exceptional construct (such as wave function collapse) to explain it. Many physicists, however, dislike the implication that there are infinitely many non-observable alternate universes.

as of 2006[update], there are no practical experiments that distinguish between Many-Worlds and Copenhagen. There may be cosmological, observational evidence.

Copenhagen interpretation

In the Copenhagen interpretation, the mathematics of quantum mechanics allows one to predict probabilities for the occurrence of various events. In the many-worlds interpretation, all these events occur simultaneously. What meaning should be given to these probability calculations? And why do we observe, in our history, that the events with a higher computed probability seem to have occurred more often? One answer to these questions is to say that there is a probability measure on the space of all possible universes, where a possible universe is a complete path in the tree of branching universes. This is indeed what the calculations give. Then we should expect to find ourselves in a universe with a relatively high probability rather than a relatively low probability: even though all outcomes of an experiment occur, they do not occur in an equal way. As an interpretation which (like other interpretations) is consistent with the equations, it is hard to find testable predictions of MWI.

Quantum suicide

There is a rather more dramatic test than the one outlined above for people prepared to put their lives on the line: use a machine which kills them if a random quantum decay happens. If MWI is true, they will still be alive in the world where the decay didn't happen and would feel no interruption in their stream of consciousness. By repeating this process a number of times, their continued consciousness would be arbitrarily unlikely unless MWI was true, when they would be alive in all the worlds where the random decay was on their side. From their viewpoint they would be immune to this death process. Clearly, if MWI does not hold, they would be dead in the one world. Other people would generally just see them die and would not be able to benefit from the result of this experiment.

The universe decaying to a new vacuum state

Any event that changes the number of observers in the universe may have experimental consequences.[62] Quantum tunnelling to new vacuum state would reduce the number of observers to zero (i.e. kill all life). Some Cosmologists argue that the universe is in a false vacuum state and that consequently the universe should have already experienced quantum tunnelling to a true vacuum state. This has not happened and is cited as evidence in favour of many-worlds.

Many-minds

The many-worlds interpretation should not be confused with the similar many-minds interpretation which defines the split on the level of the observers' minds.

Reception

There is a wide range of claims that are considered "many-worlds" interpretations. It was often claimed by those who do not believe in MWI[63] that Everett himself was not entirely clear as to what he believed; however MWI adherents (such as DeWitt, Tegmark, Deutsch and others) believe they fully understand Everett's meaning as implying the literal existence of the other worlds. Additionally, recent biographical sources make it clear that Everett believed in the literal reality of the other quantum worlds.[64] Everett's son reported that Hugh Everett "never wavered in his belief over his many-worlds theory".[65] Also Everett's reported belief in quantum immortality, requires belief in the reality of all the many-worlds represented by the components of the uncollapsed universal wavefunction.[66]

"Many-worlds"-like interpretations are now considered fairly mainstream within the quantum physics community. For example, a poll of 72 leading physicists conducted by the American researcher David Raub in 1995 and published in the French periodical Sciences et Avenir in January 1998 recorded that nearly 60% thought that the many-worlds interpretation was "true". Max Tegmark also reports the result of a poll taken at a 1997 quantum mechanics workshop.[67] According to Tegmark, "The many worlds interpretation (MWI) scored second, comfortably ahead of the consistent histories and Bohm interpretations." Other such polls have been taken at other conferences: see for instance Michael Nielsen's blog[68] report on one such poll. Nielsen remarks that it appeared most of the conference attendees "thought the poll was a waste of time". MWI skeptics (for instance Asher Peres) argue that polls regarding the acceptance of a particular interpretation within the scientific community, such as those mentioned above, cannot be used as evidence supporting a specific interpretation's validity.

A 2005 minor poll on the Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics workshop at the Institute for Quantum Computing University of Waterloo produced contrary results, with the MWI as the least favored.[69]

One of MWI's strongest advocates is David Deutsch.[70] According to Deutsch, the single photon interference pattern observed in the double slit experiment can be explained by interference of photons in multiple universes. Viewed in this way, the single photon interference experiment is indistinguishable from the multiple photon interference experiment. In a more practical vein, in one of the earliest papers on quantum computing,[71] he suggested that parallelism that results from the validity of MWI could lead to "a method by which certain probabilistic tasks can be performed faster by a universal quantum computer than by any classical restriction of it". Deutsch has also proposed that when reversible computers become conscious that MWI will be testable (at least against "naive" Copenhagenism) via the reversible observation of spin.[51]

Asher Peres was an outspoken critic of MWI, for example in a section in his 1993 textbook with the title Everett's interpretation and other bizarre theories. In fact, Peres questioned whether MWI is really an "interpretation" or even if interpretations of quantum mechanics are needed at all. Indeed, the many-worlds interpretation can be regarded as a purely formal transformation, which adds nothing to the instrumentalist (i.e. statistical) rules of the quantum mechanics. Perhaps more significantly, Peres seems to suggest that positing the existence of an infinite number of non-communicating parallel universes is highly suspect as it violates those interpretations of Occam's Razor that seek to minimize the number of hypothesized entities. Proponents of MWI argue precisely the opposite, by applying Occam's Razor to the set of assumptions rather than multiplicity of universes. In Max Tegmark's formulation, the alternative to many-worlds is the undesirable "many words", an allusion to the complexity of von Neumann's collapse postulate.

MWI is considered by some to be unfalsifiable and hence unscientific because the multiple parallel universes are non-communicating, in the sense that no information can be passed between them. Others[51] claim MWI is directly testable. Everett regarded MWI as falsifiable since any test that falsifies conventional quantum theory would also falsify MWI.[19]

According to Martin Gardner, MWI has two different interpretations: real or unreal (the latter in which the other worlds are "not real"), and claims that Stephen Hawking and Steve Weinberg both favour the unreal interpretation.[72] Gardner also claims that the nonreal interpretation is favoured by the majority of physicists, whereas the "realist" view is only supported by MWI experts such as David Deutsch and Bryce DeWitt. Hawking has said that "according to Feynman's idea", all the other histories are "equally real" as our own[73], and Tipler reports Hawking saying that MWI is "trivially true" (scientific jargon for "obviously true") if quantum theory applies to all reality.[74] In a 1983 interview Hawking also said he regarded the MWI as "self-evidently correct" but was dismissive towards questions about the interpretation of quantum mechanics, saying "when I hear of Schrödinger's cat, I reach for my gun". In the same interview he also said, "But, look: All that one does, really, is to calculate conditional probabilities—in other words, the probability of A happening, given B. I think that that's all the many worlds interpretation is. Some people overlay it with a lot of mysticism about the wave function splitting into different parts. But all that you're calculating is conditional probabilities."[75] Elsewhere Hawking contrasted his attitude towards the "reality" of physical theories with that of his colleague Roger Penrose, saying "He's a Platonist and I'm a positivist. He's worried that Schrödinger's cat is in a quantum state, where it is half alive and half dead. He feels that can't correspond to reality. But that doesn't bother me. I don't demand that a theory correspond to reality because I don't know what it is. Reality is not a quality you can test with litmus paper. All I'm concerned with is that the theory should predict the results of measurements. Quantum theory does this very successfully."[76] For his own part, Penrose agrees with Hawking that QM applied to the universe implies MW, although he considers the current lack of a successful theory of quantum gravity negates the claimed universality of conventional QM.[58]

Speculative implications

Speculative physics deals with questions also discussed in science fiction.

Quantum suicide thought experiment

It has been claimed that there is a thought experiment that would clearly differentiate between the many-worlds interpretation and other interpretations of quantum mechanics. It involves a quantum suicide machine and an experimenter willing to risk death. However, at best, this would only decide the issue for the experimenter; bystanders would learn nothing. The flip side of quantum suicide is quantum immortality.

Weak coupling

Another speculation is that the separate worlds remain weakly coupled (e.g. by gravity) permitting "communication between parallel universes".

Similarity to modal realism

The many-worlds interpretation has some similarity to modal realism in philosophy, which is the view that the possible worlds used to interpret modal claims actually exist. Unlike philosophy, however, in quantum mechanics counterfactual alternatives can influence the results of experiments, as in the Elitzur-Vaidman bomb-testing problem or the Quantum Zeno effect.

Time travel

The many-worlds interpretation could be one possible way to resolve the paradoxes [70] that one would expect to arise if time travel turns out to be permitted by physics (permitting closed timelike curves and thus violating causality). Entering the past would itself be a quantum event causing branching, and therefore the timeline accessed by the time traveller simply would be another timeline of many. In that sense, it would make the Novikov self-consistency principle unnecessary.

Many-worlds in literature and science fiction

See also: alternate history

The many-worlds interpretation (and the somewhat related concept of possible worlds) has been associated to numerous themes in literature, art and science fiction.

Some of these stories or films violate fundamental principles of causality and relativity, and are extremely misleading since the information-theoretic structure of the path space of multiple universes (that is information flow between different paths) is very likely extraordinarily complex. Also see Michael Clive Price's FAQ referenced in the external links section below where these issues (and other similar ones) are dealt with more decisively.

Another kind of popular illustration of many-worlds splittings, which does not involve information flow between paths, or information flow backwards in time considers alternate outcomes of historical events. According to the many-worlds interpretation, all of the historical speculations entertained within the alternate history genre are realized in parallel universes.[1]

See also

|

|

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Bryce Seligman DeWitt, Quantum Mechanics and Reality: Could the solution to the dilemma of indeterminism be a universe in which all possible outcomes of an experiment actually occur?, Physics Today,23(9) pp 30-40 (1970) "“every quantum transition taking place on every star, in every galaxy, in every remote corner of the universe is splitting our local world on earth into myriads of copies of itself.”"also April 1971 letters followup

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Hugh Everett Theory of the Universal Wavefunction, Thesis, Princeton University, (1956, 1973), pp 1-140

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Hugh Everett, Relative State Formulation of Quantum Mechanics, Reviews of Modern Physics vol 29, (1957) pp 454-462.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Cecile M. DeWitt, John A. Wheeler eds, The Everett-Wheeler Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics, Battelle Rencontres: 1967 Lectures in Mathematics and Physics (1968)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Bryce Seligman DeWitt, The Many-Universes Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics, Proceedings of the International School of Physics "Enrico Fermi" Course IL: Foundations of Quantum Mechanics, Academic Press (1972)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Bryce Seligman DeWitt, R. Neill Graham, eds, The Many-Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics, Princeton Series in Physics, Princeton University Press (1973), ISBN 0-691-08131-X Contains Everett's thesis: The Theory of the Universal Wavefunction, pp 3-140.

- ↑ Bryce Seligman DeWitt, R. Neill Graham, eds, The Many-Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics, Princeton Series in Physics, Princeton University Press (1973), ISBN 0-691-08131-X Contains Everett's thesis: The Theory of the Universal Wavefunction, where the claim to resolves all paradoxes is made on pg 118, 149.

- ↑ Hugh Everett, Relative State Formulation of Quantum Mechanics, Reviews of Modern Physics vol 29, (July 1957) pp 454-462. The claim to resolve EPR is made on page 462

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Stefano Osnaghi, Fabio Freitas, Olival Freire Jr, The Origin of the Everettian Heresy, Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 40(2009)97–123

- ↑ H. Dieter Zeh, On the Interpretation of Measurement in Quantum Theory, Foundation of Physics, vol. 1, pp. 69-76, (1970).

- ↑ Wojciech Hubert Zurek, Decoherence and the transition from quantum to classical, Physics Today, vol. 44, issue 10, pp. 36-44, (1991).

- ↑ Wojciech Hubert Zurek, Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical, Reviews of Modern Physics, 75, pp 715-775, (2003)

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Steven Weinberg, Dreams of a Final Theory: The Search for the Fundamental Laws of Nature (1993), ISBN 0-09-922391-0, pg 68-69

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Steven Weinberg Testing Quantum Mechanics, Annals of Physics Vol 194 #2 (1989), pg 336-386

- ↑ John Archibald Wheeler, Geons, Black Holes & Quantum Foam, ISBN 0-393-31991-1. pp 268-270

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Everett 1957, section 3, 2nd paragraph, 1st sentence

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Everett [1956]1973, "Theory of the Universal Wavefunction", chapter 6 (e)

- ↑ Zurek, Wojciech (March 2009). Quantum Darwinism. Nature Physics. http://arxiv.org/abs/0903.5082.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Everett

- ↑ "Whether you can observe a thing or not depends on the theory which you use. It is the theory which decides what can be observed." Albert Einstein to Werner Heisenberg, objecting to placing observables at the heart of the new quantum mechanics, during Heisenberg's 1926 lecture at Berlin; related by Heisenberg in 1968, quoted by Abdus Salam, Unification of Fundamental Forces, Cambridge University Press (1990) ISBN 0-521-37140-6, pp 98-101

- ↑ N.P. Landsman, "The conclusion seems to be that no generally accepted derivation of the Born rule has been given to date, but this does not imply that such a derivation is impossible in principle.", in Compendium of Quantum Physics (eds.) F.Weinert, K. Hentschel, D.Greenberger and B. Falkenburg (Springer, 2008), ISBN 3540706224

- ↑ Adrian Kent (May 5, 2009), One world versus many: the inadequacy of Everettian accounts of evolution, probability, and scientific confirmation

- ↑ Adrian Kent: Against Many-Worlds Interpretations, Int.J.Mod.Phys. A5 (1990) 1745

- ↑ Gleason, A. M. (1957). "Measures on the closed subspaces of a Hilbert space". Journal of Mathematics and Mechanics 6: 885–893. doi:10.1512/iumj.1957.6.56050. MR0096113.

- ↑ James Hartle, Quantum Mechanics of Individual Systems, American Journal of Physics, 1968, vol 36 (#8), pp. 704-712

- ↑ E. Farhi, J. Goldstone & S. Gutmann. How probability arises in quantum mechanics., Ann. Phys. (N.Y.) 192, 368-382 (1989).

- ↑ Pitowsky, I. (2005). Quantum mechanics as a theory of probability. arXiv:quant-ph/0510095.

- ↑ Deutsch, D. (1999). Quantum Theory of Probability and Decisions. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A455, 3129–3137. [1].

- ↑ David Wallace: Quantum Probability and Decision Theory, Revisited

- ↑ David Wallace. Everettian Rationality: defending Deutsch’s approach to probability in the Everett interpretation. Stud. Hist. Phil. Mod. Phys. 34 (2003), 415-438.

- ↑ David Wallace (2003), Quantum Probability from Subjective Likelihood: improving on Deutsch's proof of the probability rule

- ↑ David Wallace, 2009,A formal proof of the Born rule from decision-theoretic assumptions

- ↑ Simon Saunders: Derivation of the Born rule from operational assumptions. Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. A460, 1771-1788 (2004).

- ↑ Simon Saunders, 2004: What is Probability?

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 David J Baker, Measurement Outcomes and Probability in Everettian Quantum Mechanics, Studies In History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies In History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, Volume 38, Issue 1, March 2007, Pages 153-169

- ↑ H. Barnum, C. M. Caves, J. Finkelstein, C. A. Fuchs, R. Schack: Quantum Probability from Decision Theory? Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. A456, 1175-1182 (2000).

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Merali, Zeeya (2007-09-21). "Parallel universes make quantum sense". New Scientist (2622). http://space.newscientist.com/article/mg19526223.700-parallel-universes-make-quantum-sense.html. Retrieved 2007-10-20 (Summary only).

- ↑ Breitbart.com, Parallel universes exist - study, Sept 23 2007

- ↑ Perimeter Institute, Seminar overview, Probability in the Everett interpretation: state of play, David Wallace - Oxford University, 21 Sept 2007

- ↑ Perimeter Institute, Many worlds at 50 conference, September 21-24, 2007

- ↑ Wojciech H. Zurek: Probabilities from entanglement, Born’s rule from envariance, Phys. Rev. A71, 052105 (2005).

- ↑ M. Schlosshauer & A. Fine: On Zurek's derivation of the Born rule. Found. Phys. 35, 197-213 (2005).

- ↑ Lutz Polley, Position eigenstates and the statistical axiom of quantum mechanics, contribution to conference Foundations of Probability and Physics, Vaxjo, Nov 27 - Dec 1, 2000

- ↑ Lutz Polley, Quantum-mechanical probability from the symmetries of two-state systems

- ↑ Everett FAQ "Is many-worlds a local theory?"

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Mark A. Rubin, Locality in the Everett Interpretation of Heisenberg-Picture Quantum Mechanics, Foundations of Physics Letters, 14, (2001) , pp. 301–322, arXiv:quant-ph/0103079

- ↑ Paul C.W. Davies, Other Worlds, chapters 8 & 9 The Anthropic Principle & Is the Universe an accident?, (1980) ISBN 0-460-04400-1

- ↑ Paul C.W. Davies, The Accidental Universe, (1982) ISBN 0-521-28692-1

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Everett FAQ "Does many-worlds violate Ockham's Razor?"

- ↑ Tegmark, Max The Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics: Many Worlds or Many Words?, 1998. To quote: "What Everett does NOT postulate: “At certain magic instances, the world undergoes some sort of metaphysical 'split' into two branches that subsequently never interact.” This is not only a misrepresentation of the MWI, but also inconsistent with the Everett postulate, since the subsequent time evolution could in principle make the two terms...interfere. According to the MWI, there is, was and always will be only one wavefunction, and only decoherence calculations, not postulates, can tell us when it is a good approximation to treat two terms as non-interacting."

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 Paul C.W. Davies, J.R. Brown, The Ghost in the Atom (1986) ISBN 0-521-31316-3, pp. 34-38: "The Many-Universes Interpretation", pp83-105 for David Deutsch's test of MWI and reversible quantum memories

- ↑ Christoph Simon, 2009, Conscious observers clarify many worlds

- ↑ Arnold Neumaier's comments on the Everett FAQ, 1999 & 2003

- ↑ Everett [1956] 1973, "Theory of the Universal Wavefunction", chapter V, section 4 "Approximate Measurements", pp. 100–103 (e)

- ↑ Henry Stapp, The basis problem in many-world theories, Canadian J. Phys. 80,1043–1052 (2002) [2]

- ↑ Harvey R Brown and David Wallace, Solving the measurement problem: de Broglie-Bohm loses out to Everett, Foundations of Physics 35 (2005), pp. 517-540. [3]

- ↑ Mark A Rubin (2005), There Is No Basis Ambiguity in Everett Quantum Mechanics, Foundations of Physics Letters, Volume 17, Number 4 / August, 2004, pp 323-341

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Penrose, Roger (August 1991). "Roger Penrose Looks Beyond the Classic-Quantum Dichotomy". Sciencewatch. http://www.sciencewatch.com/interviews/roger_penrose2.htm. Retrieved 2007-10-21.

- ↑ Everett FAQ "Does many-worlds violate conservation of energy?"

- ↑ Everett FAQ "How do probabilities emerge within many-worlds?"

- ↑ Everett FAQ "When does Schrodinger's cat split?"

- ↑ Can Quantum Cosmology Give Observational Consequences of Many-Worlds Quantum Theory? by Don N. Page

- ↑ Jeffrey A. Barrett, The Quantum Mechanics of Minds and Worlds, Oxford University Press, 1999. According to Barret (loc. cit. Chapter 6) "There are many many-worlds interpretations."

- ↑ Peter Byrne, The Many Worlds of Hugh Everett III: Multiple Universes, Mutual Assured Destruction, and the Meltdown of a Nuclear Family, ISBN 978-0199552276

- ↑ Aldhous, Peter (2007-11-24). "Parallel lives can never touch". New Scientist (2631). http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg19626311.800-interview-parallel-lives-can-never-touch.html. Retrieved 2007-11-21 .

- ↑ Eugene Shikhovtsev's Biography of Everett, in particular see "Keith Lynch remembers 1979-1980"

- ↑ Max Tegmark on many-worlds (contains MWI poll)

- ↑ Michael Nielsen: The interpretation of quantum mechanics

- ↑ Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics class survey

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 David Deutsch, The Fabric of Reality: The Science of Parallel Universes And Its Implications, Penguin Books (1998), ISBN 0-14-027541-X

- ↑ David Deutsch, Quantum theory, the Church-Turing principle and the universal quantum computer, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A 400, (1985), pp. 97–117

- ↑ A response to Bryce DeWitt, Martin Gardner, May 2002

- ↑ Award winning 1995 Channel 4 documentary "Reality on the rocks: Beyond our Ken" [4] where, in response to Ken Campbell's question "all these trillions of Universes of the Multiverse, are they as real as this one seems to be to me?" Hawking states "Yes.... According to Feynman's idea, every possible history (of Ken) is equally real"

- ↑ Tipler, Frank J. (2006-11-26). "What About Quantum Theory? Bayes and the Born Interpretation". arXiv, Cornell University. http://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0611245v1. Retrieved 2007-10-20. Page 1: "It is well-known that if the quantum formalism applies to all reality, both to atoms, to humans, to planets and to the universe itself then the Many Worlds Interpretation is trivially true (to use an expression of Stephen Hawking, expressed to me in a private conversation)."

- ↑ Ferris, Timothy (1997). The Whole Shebang. Simon & Schuster. pp. 345. ISBN 978-0684810201.

- ↑ Hawking, Stephen; Roger Penrose (1996). The Nature of Space and Time. Princeton University Press. pp. 121. ISBN 978-0691037912.

Further reading

- Jeffrey A. Barrett, The Quantum Mechanics of Minds and Worlds, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1999.

- Julian Brown, Minds, Machines, and the Multiverse, Simon & Schuster, 2000, ISBN 0-684-81481-1

- Paul C.W. Davies, Other Worlds, (1980) ISBN 0-460-04400-1

- James P. Hogan, The Proteus Operation (science fiction involving the many-worlds interpretation, time travel and World War 2 history), Baen, Reissue edition (August 1, 1996) ISBN 0671877577

- Adrian Kent, One world versus many: the inadequacy of Everettian accounts of evolution, probability, and scientific confirmation * Asher Peres, Quantum Theory: Concepts and Methods, Kluwer, Dordrecht, 1993.

- Andrei Linde and Vitaly Vanchurin, How Many Universes are in the Multiverse?

- Stefano Osnaghi, Fabio Freitas, Olival Freire Jr, The Origin of the Everettian Heresy, Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 40(2009)97–123. A study of the painful three-way relationship between Hugh Everett, John A Wheeler and Niels Bohr and how this affected the early development of the many-worlds theory.

- Mark A. Rubin, Locality in the Everett Interpretation of Heisenberg-Picture Quantum Mechanics, Foundations of Physics Letters, 14, (2001) , pp. 301–322, arXiv:quant-ph/0103079

- Frank J. Tipler, Testing Many-Worlds Quantum Theory By Measuring Pattern Convergence Rates

- David Wallace, Harvey R. Brown, Solving the measurement problem: de Broglie-Bohm loses out to Everett, Foundations of Physics, arXiv:quant-ph/0403094

- David Wallace, Worlds in the Everett Interpretation, Studies in the History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 33, (2002), pp. 637–661, arXiv:quant-ph/0103092

- John A. Wheeler and Wojciech Hubert Zurek (eds), Quantum Theory and Measurement, Princeton University Press, (1983), ISBN 0-691-08316-9

External links

- Everett's Relative-State Formulation of Quantum Mechanics - Jeffrey A. Barrett's article on Everett's formulation of quantum mechanics in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Many-Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics - Lev Vaidman's article on the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Michael C Price's Everett FAQ -- a clear FAQ-style presentation of the theory.

- The Many-Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics - a description for the lay reader with links.

- Against Many-Worlds Interpretations by Adrian Kent

- Many-Worlds is a "lost cause" according to R. F. Streater

- The many worlds of quantum mechanics John Sankey

- Max Tegmark's web page

- Henry Stapp's critique of MWI, focusing on the basis problem Canadian J. Phys. 80,1043–1052 (2002).

- Everett hit count on arxiv.org

- Many Worlds 50th anniversary conference at Oxford

- "Many Worlds at 50" conference at Perimeter Institute

- Scientific American report on the Many Worlds 50th anniversary conference at Oxford

- Highfield, Roger (September 21, 2007). Parallel universe proof boosts time travel hopes. The Daily Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/earth/main.jhtml?xml=/earth/2007/09/21/sciuni121.xml. Retrieved 2007-10-26.

- HowStuffWorks article

- Physicists Calculate Number of Parallel Universes Physorg.com October 16, 2009.

![\lang O[i]|O[j]\rang = \delta_{ij}](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/75da0bc205119ea07e9111ae9f568b04.png)